I have often talked about the excitement I feel when an exceptional antique crosses my path, and this 18th century mantlepiece by Pietro Bossi is no exception.

The One and Only Pietro Bossi, the Master of Inlay

27 April 2018

The centrepiece of a magnificent late 18th Century Irish white statuary marble chimneypiece, inlaid with coloured scagliola. Attributed to the Dublin workshops of Pietro Bossi.

As an antique dealer and designer I am always drawn to the craftsmanship of a piece, and Pietro Bossi’s work undoubtedly exhibits some of the finest stucco and scagliola work. His creations are an art in itself.

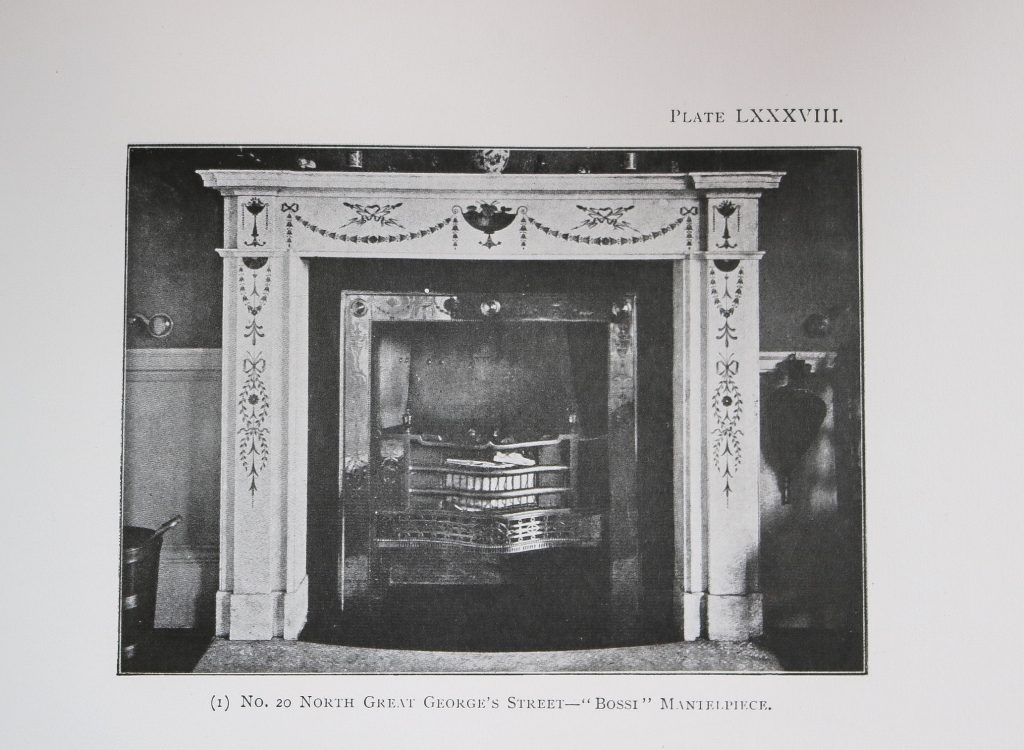

This mantle came from Oakley Park, built in 1724, County Carlow, Ireland. There are two near identical chimneypieces in existence; the first is in the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, having being removed from one of the houses that was demolished to make way for the construction of the National Library in 1886. The second is in 6 Randolph Cliff, Edinburgh, which was removed in 1905/6, from 20 North Great George Street, Dublin and illustrated in the Georgian Society Records published in 1909.

The near identical Bossi mantlepiece from No.20 North Great George’s Street, illustrated in the Georgian Society Records published in 1909.

The process and technique of his scagliola and stucco work, it is said, was a closely guarded secret – so much so, he worked alone during the day and at night he would scatter sawdust around his work to reveal the treachery of any foot that set close! It is understood that Bossi came from a distinguished line of stucco workers (Stuccodores) near Como, Northern Italy, and his work brought him to Dublin in the late 18th Century (1785-1798).

Initially the process of scagliola, which became popular in Italy in the seventeenth century, was used an an economic alternative to more costly marbles. ‘Scagliola’ (from the Italian for ‘chips’) is a technique that involves manipulating pigmented plaster, modified with animal glue, to resemble inlays in marble and ornamental hard stones. It began with the Romans, with examples of the earliest wall-painting seen in Pompeii and Herculaneum showing simple dados and panels imitating marble. The scagliola process was used also to veneer walls and floors, owing to its hardwearing nature. As the quality of the technique increased, it became very difficult to tell the difference between scagliola and real stone.

The dexterity of the detailing (shown above) became a means of identification for the work of Bossi. His technique was exceptional, being able to represent graduated colour and three dimensional depth with the purest of subtlety. Like any work of art, one could sit for hours tracing the exquisitely finely drawn fruits and flowers, and following the nuances of his hand.

I always find that when a piece pre-dates machinery, it holds a deeper resonance, especially when observing the hand tooled workings of an antique chimneypiece. When purchasing an antique chimneypiece of this nature it becomes evident that you are not just buying a surround, but a unique work of art – indeed, a masterpiece.