If collections are joined by an ‘interaction of opportunity’, then nothing compares to the chance of visiting one of the finest art collection’s of all: ‘Charles I: King and Collector‘ – the current exhibition at the Royal Academy.

Charles I: The Ultimate Collector and Doomed King of Culture.

30 March 2018

One of the most celebrated antiquities in the collection, formerly part of the celebrated ‘Gonzaga’ collection, the Ancient Roman, second century AD sculpture ‘Aphrodite, (The Crouching Venus)’

What a privilege to behold! What a collection! The finest ever collated by a King but one that was broken- up in 1649 by the overthrow of the King by the English people and his resented parliament. There would be no forgiveness for a monarch who had driven England, Scotland and Ireland into Civil War and wouldn’t accept a constitutional monarchy. The only time in history an English King was tried for treason and beheaded. His art collection was sold just afterwards in a Commonwealth sale and dispersed for ever more…until this year, almost four hundred years later, when a proportion of the original has been reunited.

‘Philip IV’ by Velázquez.

The Royal Academy’s exhibition is an extraordinary feat of reconstruction. Made possible from the evidence of two historical documents recorded by the Dutch artist and the keeper of the King’s collection Van Der Doort.The 1639 inventory of Whitehall palace and the 1649 inventories of the Commonwealth sale. In his reign, Charles I, amassed the most extraordinary collection of ancient sculptures, Italian Renaissance paintings and commissioned great works of art including the Mortlake tapestries. The collection changed the perception of art in England, creating an huge influence on 17th century artists and reflecting the social and political power of the King. Throughout Europe his collection was revered. Acquisition symbolised power and authority. But not enough to save him.

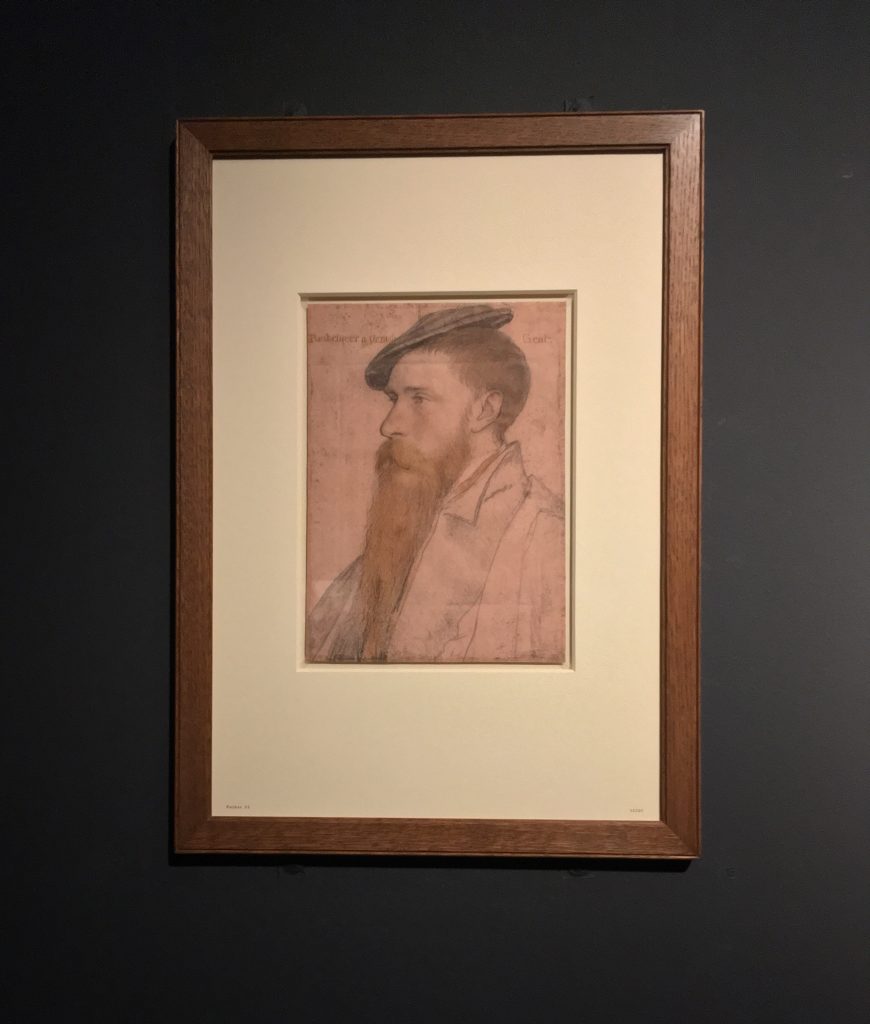

Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait of Derich Born. 1533.

Twelve resplendent rooms of the finest masterpieces ever created, exquisitely curated. The experience is a rich and resplendent one. From Ancient Roman sculpture to works by Titian, Van Dyck, Holbein and Mantegna’s nine colossal paintings ‘Triumphs of Caesar‘ – the highlight of the Gonzaga collection that the King acquired in 1629.

His great aide: Nicholas Lanier, Master of the King’s Music negotiated in buying the Gonzaga collection: one of the most important European Art collections of Italian Renaissance and Antique Roman sculptures for the King. The three ancient Roman busts above depict: Livia Drusilla, mid-second century AD, Antinous, first century AD, and the Bust of a Young Man, mid-second century AD.

King Charles I was born into an highly cultured environment but his passion was confirmed in 1623 when he took a trip to Spain with one of his greatest allies and knowledgable collectors: the 1st Duke of Buckingham. The visit was an attempt to negotiate marriage to the sister of King Philip IV of Spain. A passion was ignited – not however with the Infanta Maria Anna of Spain but for the Habsburg art collection that contained works by Titian and Veronese. A passion began for collecting and commissioning the most important art, sculpture and tapestries of the day, which he would fervently share with his future wife, Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France.

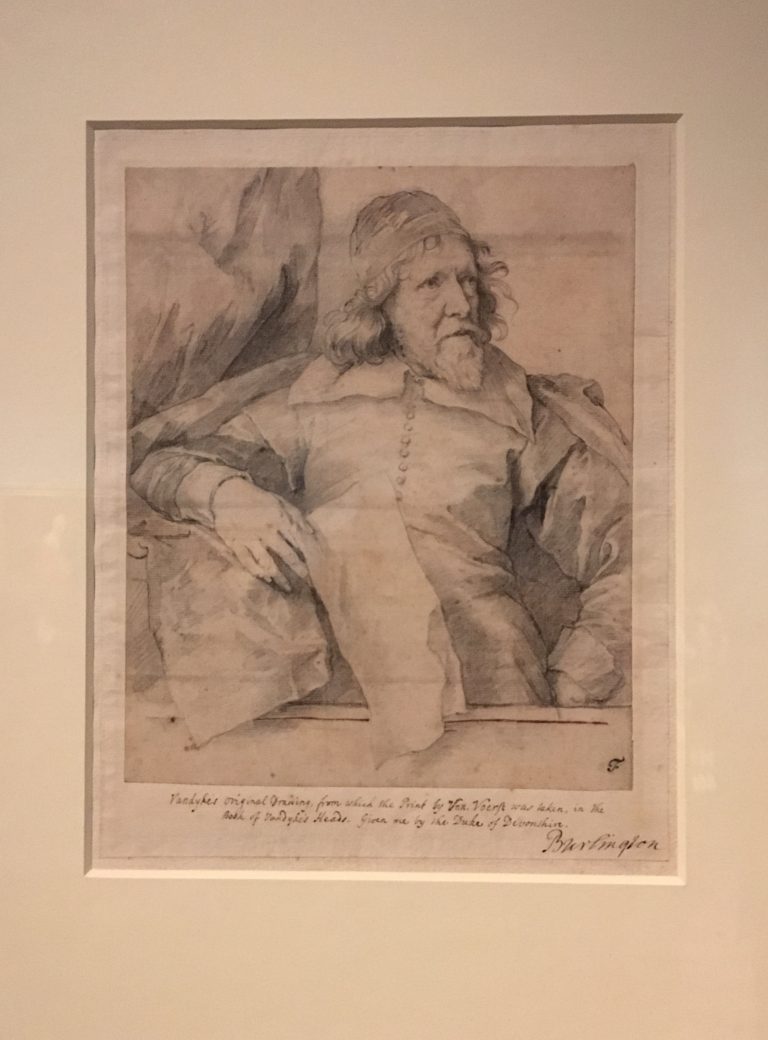

Inigo Jones by Anthony Van Dyck.

The importance of his trusted experts, advisers, negotiators and European agents, through whom he was able to acquire much of his celebrated collection should not be underestimated. They had travelled and seen the home of art: Rome. Inigo Jones had travelled widely in Italy in the 17th century and introduced classical architecture and Italian Renaissance to England. He was one of the most important advisers to the King, exerting significant influence and unique cultural expertise. Not only was he appointed Surveyor of the Kings works but he was responsible for the architecture of the most important buildings during King Charles I reign.

Many of the paintings were gifts, some were peace offerings. In 1629 Rubens: the artistic advisor, painter and diplomat to the Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga, visited England on behalf of the Spanish court to negotiate a peace treaty. In this time he painted ‘Peace and war’ which he gifted to King Charles I.

‘Charles I and Henrietta Maria with Prince Charles and Princess Mary‘ 1632 by Van Dyck.

Van Dyck changed the ‘face’ of portraiture. He was the most important portrait artist of the period and worked exclusively for the Royal family and the English aristocracy. The social order of visiting was also reversed in this relationship, as it is recorded that King Charles I actually visited Van Dyck’s house In Blackfriars to view his paintings. His depictions of the King and his wife and family hold a poetic resonance and exude a visual narrative.

The’ Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist‘, attributed to Raphael hung in the Kings bed chamber. One of his most beloved pieces and of it’s previous owner, Philip IV of Spain, who named it ‘La Perla’- ‘ the pearl’ of his collection. This was one of the most expensive in the sale following his death and sold for the then staggering £800.

Hans Holbein the Younger, ‘William Reskimer’ (1532-4) that hung in the King’s Apartments.

The most valuable works in the royal collection were the Mortlake tapestries and clearly marked King Charles I status as a great connoisseur. Raphael’s cartoons of the ‘Acts of the Apostles’ were the source of the King’s inspiration behind his commission to create the most magnificent tapestries, which took ten years and further established England as a centre of art excellence. The cost to create them was huge- the set of seven colossal (286 x 311 cm) works of art, cost approximately £4,500 and they were judged to be the finest tapestries ever made The, wool, silk and gilt- metal wrapped thread masterpieces are magnificent in every way and were so precious that they were sold even before the Commonwealth sale took place.

Nineteen years, after King Charles I death, during the restoration, his son Charles II tried to recover as much as his fathers collection. His father, whom Rubens described as ‘the finest amateur (lover) of paintings amongst the princes of the world.’ Nothing seems to serve the phrase ‘once in a lifetime exhibition’ more so than this extraordinary show and it is with great thanks to her Majesty, the Queen, who lent the majority of the collection and to all the museums and private collectors around the world who agreed to reuniting one of the finest collection’s in history.