Sir Robert Taylor started out as a sculptor but by the middle of the eighteenth century he had become the most successful architect of his generation. He was appointed Surveyor and Architect to the Bank of England and the Admiralty among others, while also designing residences for aristocrats, wealthy merchants and bankers — both town houses and country mansions. As a consequence, the bulk of his buildings were in London and the Home Counties, and sadly they have been either demolished, redeveloped, bombed or altered over the past 250 years.

A Highly Important 18th Century Chimneypiece by Sir Robert Taylor.

10 January 2020

Detail from Jamb's G357, a highly important 18th century chimneypiece by Sir Robert Taylor

This exceptional chimneypiece is of great historical importance. A rare example of English Rococo, it has the added distinction of being by Sir Robert Taylor, and so it carries huge architectural significance. The English Rococo enjoyed the briefest flowering before giving way to Graeco-Roman Neoclassicism later in the 18th century. Consequently, pure English Rococo chimneypieces are usually only found in important listed buildings. During the 1750s, Taylor produced some of the finest chimneypieces in this fashionable new style. Only a handful are known to have survived. This one perfectly illustrates his assured touch. Eschewing unnecessary and superfluous decoration, he produced a beautifully balanced, flowing design.

During the 1750s, Taylor embraced the fashion for the Rococo, and produced some of the finest chimneypieces in that style. Only a handful are known to have survived the depredations of the intervening years, and this is the supreme example of them all — executed in fine-grained limestone, and displaying perfectly Taylor’s mastery of sculpture and design.

Researching this chimneypiece from our antique collection entailed delving into the archives of the Taylorian Institute in Oxford and hunting for clues in the vast repository of the British Library. Only then was it finally possible to determine beyond doubt that it was indeed by the man himself, and there is a powerful case for it being from the dining room of 36 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London.

Robert Taylor was born in 1714, the son of Robert Taylor the Elder (‘the great stonemason of his time’, according to Walpole). Aged 18, he was apprenticed to Sir Henry Cheere. He went off to study in Rome but had to return home when his father died. With war raging in Europe, Taylor made the perilous journey back to England disguised in a friar’s habit (which he retained as a keepsake all his life), in the company of a monk.

Sir Robert Taylor after William Miller, watercolour, based on a work of circa 1782

Initially, he specialised in sculpture and monuments, and he was chosen to carve the pediment of Mansion House, beating Roubiliac and his old master Cheere to the commission. His prize work in this field was the magnificent monument to LT General Guest in Westminster Abbey, dated 1751. In due course, Taylor’s own memorial would be placed in Poet’s Corner, the inscription pronouncing that ‘his works entitle him to a distinguished rank in the first order of British architects’.

Sometime around 1750 he switched his focus to architecture, quickly winning a succession of commissions from influential figures. His pupils included John Nash and Samuel Pepys Cockerell. So successful was his practice that when he died in 1788 he left an estate of £180,000 — in contrast, William Kent left £10,000, James Gibbs £25,000, and Christopher Wren £50,000.

The Rotunda at the Bank of England Illustration for Engravings, Drawings and Paintings in the Bank of England (1928)

He was appointed Surveyor and Architect of the Bank of England, and designed the main buildings, including the Rotunda and Court Room. It was his statue of Britannia that would earn the bank its nickname ‘the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street’. He brought an innovative twist to Palladian design, was a master of the arcade, bay and dome, and had an innate understanding of the interplay between space and light. His chimneypieces in the 1750s were some of the finest examples of pure English Rococo, evolving into the Neo-Classical in later buildings. (Another legacy is the Lord Mayor’s State Coach, still used annually for the Lord Mayor’s Show.)

Taylor’s enormous contribution to London’s streetscape, little known or appreciated, came as a consequence of his role jointly drafting the Building Act of 1774 with George Dance the Younger. The provisions of the Act, aimed at reducing fire risk, controlled the character and material of buildings for decades, and were pivotal in creating the elegance and harmony of the city’s Georgian, Regency and early Victorian squares, terraces and streets.

At the time of the Act, Taylor was working on Ely House in Mayfair, an ingenious building whose facade perfectly illustrates his deft touch and attention to detail. Here he created shallow recesses between it and its neighbours — a seemingly insignificant device but one that gives the house a sense of depth and detachment, allowing cornices to return unimpeded, and the string courses and stone blocks to be silhouetted. By repeating this visual trick in the upper sections, with increased gaps, he creates a taper, giving the building its sense of vitality and upward movement.

Taylor executed a number of commissions for the Duke of Grafton, including Grafton House in Piccadilly, which was demolished in 1966. Of the 14 houses he built in Grafton Street, Mayfair, four survive, early examples of his principles put into practice, with balanced and elegant frontages that belie the grand interiors within.

One of these was built for Admiral Lord Howe, for whom Taylor and his pupil Samuel Pepys Cockerell later designed Admiralty House off Whitehall. Taylor was knighted in 1784, having been appointed surveyor for a number of bodies and institutions, including the Admiralty, Greenwich Hospital and Customs and Excise. So why, given his standing then, has his reputation been somewhat overshadowed by the likes of Robert Adam, Sir John Soane, Sir Henry Cheere and Sir William Chambers? Unlike many of his contemporaries, Taylor did not publish a volume, catalogue or corpus of his work, which undoubtedly lowered his profile after he died. Furthermore, comprehensive records of his work have almost completely vanished, their fate a total mystery.

A chimneypiece design by Taylor, circa 1750, in a folio of twelve drawings, held at the Taylorian Institute

The Taylorian Institute in Oxford, which was endowed by him and established in 1835, does hold a handful of chimneypiece designs, a collection of sketches for monuments and a volume of various studies of geometry and perspective. But nothing else is known to have survived, other than a handful of drawings, notably for a dining room at Trewithen House in Cornwall and the bridge at Maidenhead.

Add then there is the destruction wrought by demolition, alteration and wartime bombing. Sir John Soane, in particular, bears some responsibility here, having swept away much of Taylor’s Bank of England when he remodelled it. Consequently, few of his London projects survive, and virtually none of his buildings anywhere remain in the form he intended.

In recent decades, Taylor’s work has been re-evaluated, and his contribution to the development of 18th century architecture recognised, thanks to monographs by the architectural historians Marcus Binney and Christopher Hussey. Their analyses have thankfully restored him to his rightful place, alongside Robert Adam, Sir William Chambers and Thomas Paine, in the pantheon of English and Scottish architects of that era.

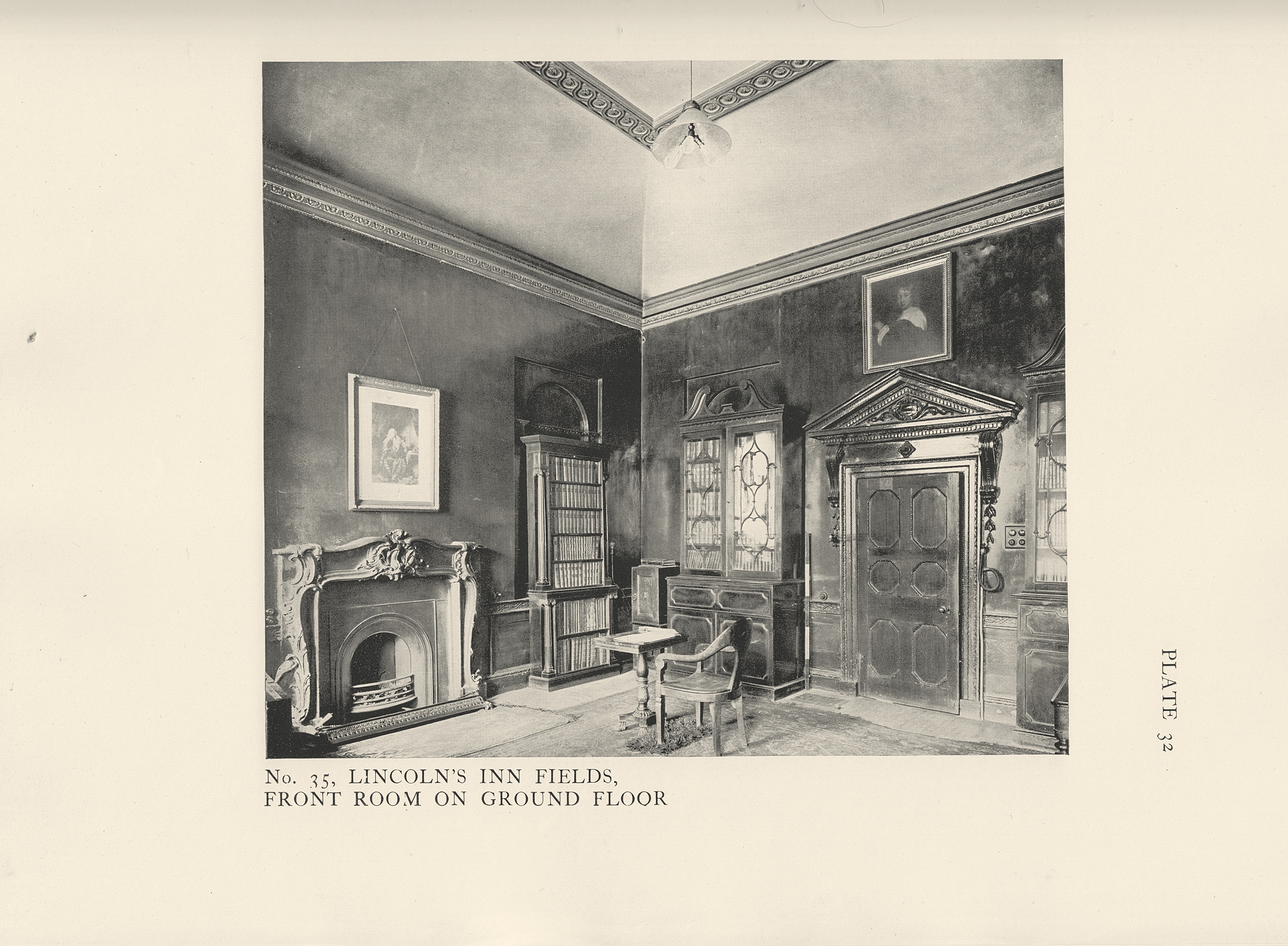

And yet so much of his output has been lost — not least his Rococo chimneypieces. There are just six that we know of. A further three are shown in photographs from 35 Lincoln’s Inn Fields taken during the Survey of London in 1912. However, that building was destroyed in the Blitz, chimneypieces and all. Nonetheless, those black-and-white photographs of the interior offer us some tantalising clues. We know, for example, that there was was one pure English Rococo chimneypiece in the front room on the ground floor, one in the middle room on the first floor, and a large stone one in the basement kitchen of all places.

From Survey of London Vol.III, St. Giles-in-the-Fields — Part I

The original buildings on this site were erected in 1659. Apparently there were four individual houses, but by 1757 they had disappeared from the rate books — one having been empty for 29 years, and two of the others for 15 years. In their place, two houses were built, with Taylor as the architect, starting in 1754. They had one centrally placed flight of stairs that bifurcated to serve the properties, which had been designed to appear as one composition.

Number 35 had an oval staircase with very fine wrought-iron balustrade, with a baroque feel more reminiscent of the architect’s early work. Taylor used his characteristic octagonal glazing, with the same geometric theme continued in the interiors, incorporating octagonal panels in the doors and panelling. His use of arches, blind arcading, apses and domes was to be repeated in much of his later work. The rear extension is pedimented, and there are Venetian and Diocletian windows with octagonal glazing. There is no record of the interior of 36 as it was demolished in 1859, though we know from the floor plans that it and number 35 differed internally, despite the facade being balanced and unified.

From Survey of London Vol.III, St. Giles-in-the-Fields — Part I

As I mentioned, when the property was surveyed and photographed in 1912 there was a Rococo stone chimneypiece in the basement with a Victorian cooking range within. And yet it is inconceivable that Taylor would have installed the grandest of Rococo mantels in one of the humblest of rooms, the kitchen. The explanation lies in the survey’s photographs and script. The chimneypiece in the ground-floor middle room is not featured, the room having been partitioned to make offices. That, then, is why it was in the basement — it was relocated when the room was partitioned. The scale, ornamental value and imagery (vine leaves, grapes and mask of Bacchus) indicate it had once been in the dining room.

As numbers 35 and 36 had been planned as a pair, it is reasonable to assume they would have shared similarities and artistic references — including chimneypieces. Close inspection reveals the form and enrichment of the stone chimneypiece in the 1912 photograph to correspond uncannily with this one, apart from the mask. Where the one at number 35 depicts an ageing Bacchus, his face puffy, bearded and middle-aged, this shows a more youthful Dionysus (his Greek equivalent) unscarred by years of indulgence. That raises the intriguing possibility that this chimneypiece was originally located in the dining room of 36 Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Number 36 was demolished in 1859, perversely, since the symmetry of Taylor’s composition was destroyed in the process. However, one would have expected its chimneypieces to have survived. Interestingly, a number of those in the principal rooms of Admiralty House — Taylor’s last project, which his protégée Samuel Pepys Cockerell completed after his death — came from other notable buildings, including the Piccadilly home of Lord Egremont, Sir Frederick Page’s house in Blackheath, and York House. Salvage and re-use have a long-established pedigree. And so it is not unreasonable to conclude that this exceptional chimneypiece is the missing twin of the Bacchus mantel photographed in 1912. The evidence is compelling, though where it has been in the years since the nineteenth century is something of a mystery. When it was acquired it had been removed from a property that was not subject to listing restrictions. It was clear it had only been there for a limited period of time because the chimneypiece had been repaired and restored relatively recently and overpainted with a modern paint finish. What is certain, however, is that it is by Sir Robert Taylor. A work of art with a flow, fineness of detail and presence that few could match, it is a tangible reminder of his skill as a sculptor and designer deserving of his place in the uppermost rank of eighteenth century architects.